What did I listen to?

Vaughan Williams, Symphony No.3 ‘The Pastoral’

Which recording(s)?

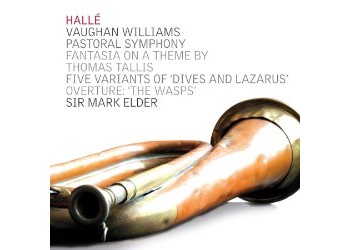

Hallé Orchestra, Sir Mark Elder, Sarah Fox (soprano)

London Symphony Orchestra, Bernard Haitink, Amanda Roocroft (soprano)

Why did I choose it?

Last week I watched an excellent BBC4 documentary in which Amanda Vickery and Tom Service explored the friendship between Holst and Vaughan Williams. This symphony featured briefly in it, and it reminded me that there is so much more to Vaughan Williams than folksong, hymn tunes and the Lark Ascending. I think it’s this ingrained image of his music that has held me back from exploring the symphonies, and it’s high time I did something about that.

What do I already know or expect?

The ‘Pastoral’ in the title is apparently a bit of a red-herring, because this symphony is in fact Vaughan Williams’ response to his experiences in World War I. He was too old to be called up for military service, but nonetheless he volunteered, serving on the front as an ambulance driver. We think a lot about the horror of life in the trenches and men being mown down as they were sent over the top, but what about the men who had to, literally, pick up the pieces? They must have seen unspeakable horrors as they retrieved and transported broken men away from the front.

Vaughan Williams wrote that much of the symphony was ‘incubated’ on a hill above Ecoivres where he used to climb to watch the magnificent sunsets. I imagine the contrast between the unchanging beauty of the sunset throwing the last gentle light of dusk onto the industrial carnage below, and I wonder whether there’ll be some sense of that in the symphony. There’s a trumpet solo in the second movement as Vaughan Williams remembers hearing the sound of a bugler practising: even before hearing the music itself, I am finding it very moving to think of that soldier, perhaps little more than a boy, who could be destroyed at any moment, playing on into the falling darkness.

Impressions from the first hearing

I’m so glad I listened to this – what a great start to my project. It’s powerfully unsettling, particularly in the first two movements, with restless, undulating strings, and sudden changes of mood and colour with bursts of light that are then suddenly swallowed up in darkness. It reminds me of the feeling you get when you lie awake chasing elusive thoughts around in a night of insomnia. The trumpet solo at the end of the second movement is mesmerising and instead of feeling poignant as I expected, it offers a moment of tranquillity which ends with the fading sunlight flashing off the bell of the bugle.

There’s a presence of open landscapes in the first two movements, but perhaps the ‘Pastoral’ bit of the title could also refer to the folksong in the third movement (in the spirit of this project, I’ve not yet looked up what the tune is, but I assume Vaughan Williams is quoting something). It emerges out of the symphony’s most martial music, as the movement opens angrily with pounding guns, and a battle of light against dark as a flute and harp briefly try to push through. This dance also reminds me of the way Mahler or Shostakovich use traditional songs in their symphonies: there’s an element of grotesqueness to it – it suggests men in the trenches bitterly whistling tunes and thinking of what they’ve left behind.

The final movement opens with rumbling timpani and a wordless soprano solo. It’s a truly bleak moment, the lonely voice of a woman crying out her lament in a grief that goes beyond what can be expressed in words. This movement is surprisingly cinematic too – soaring strings, maybe offering surges of hope, but also returning at times to the mood of the first two movements? I feel that I need to listen again to follow the trajectory of this final movement. The symphony ends with the soprano solo, but this time accompanied by a whispery violin sustaining a single high note, and creating a completely different atmosphere – it’s not a lament now, and as the violin disappears into the ether there’s finally peace of a sort. We’ve heard Vaughan Williams do that before – is he intentionally reflecting on the Lark Ascending, a piece written just before the world exploded?

That ending brings me to one other thought, which is that there is so much that is recognisably Vaughan Williams in this, his musical voice is ever-present. That characteristic dense string sound, the high violin solo, the folk-inspired melodies, the modal harmonic language and the sudden landings on dark chords that plunge a dagger into the heart

How many times did I listen?

Three times – twice to the Hallé and once to the LSO

Any more thoughts from repeat hearings?

The more I listened, the more I grew to love this. I became more conscious of the ebb and flow of the first two movements, and of the tenderness of the second movement, and had time to admire how Vaughan Williams gently eases the solo passages in and out of the texture throughout the symphony. The more I hear the trumpet solo, the more in awe of it I am, thinking of the power and control that the player must need to sustain such long, quiet notes, and on repeat listenings I see how the horn solo pre-empts the trumpet. I’ve discovered that the folksong, surprisingly, isn’t a quote, at least not that I can find any reference to, and I did enjoy the bravado that Haikink injects into this passage. My final thought is that with the first soprano solo, Vaughan Williams has exquisitely judged just how much anguish we can bear – just as I think I can’t take any more, the strings begin their act of healing.

Buy stream or drop?

Definitely a buy – it was on my ipod by the time I’d finished writing this post. I’ve bought the Hallé album because it also has other nice things on it, including the lovely Five variants of Dives and Lazarus.